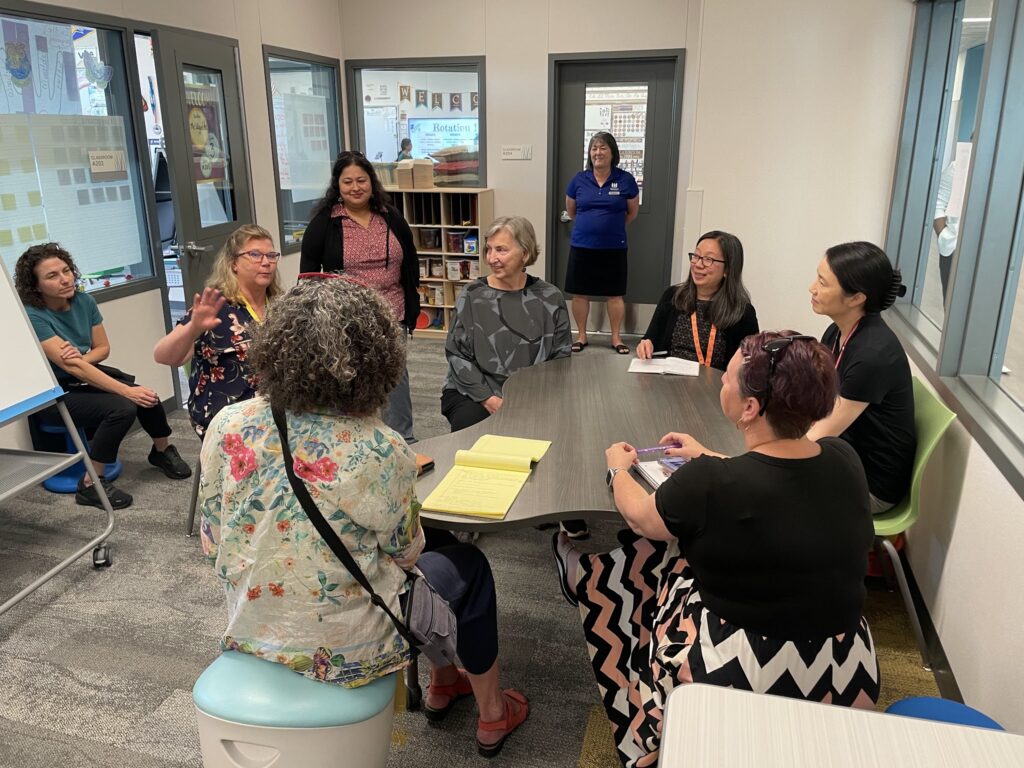

On a recent Wednesday morning, a group of K-12 educators and Stanford researchers gathered in an empty classroom at Abram Agnew Elementary School in San Jose, California. The group included elementary classroom teachers, academic resource specialists from the elementary and high schools, two principals, researchers from three Stanford education labs, and representatives from the Stanford Teacher Education Program (STEP). This powerhouse crew was the steering committee of the Stanford-Santa Clara Research Practice Learning Partnership (RPLP), working together to build new models for inclusive education.

The RPLP is a collaboration between the Stanford Accelerator for Learning’s initiative for Learning Differences and the Future of Special Education (LDI) and the Santa Clara Unified School District (SCUSD), signed in October 2022 by Professor Elizabeth Kozleski, faculty co-director of LDI, and Kathie Kanavel, assistant superintendent for educational services at SCUSD.

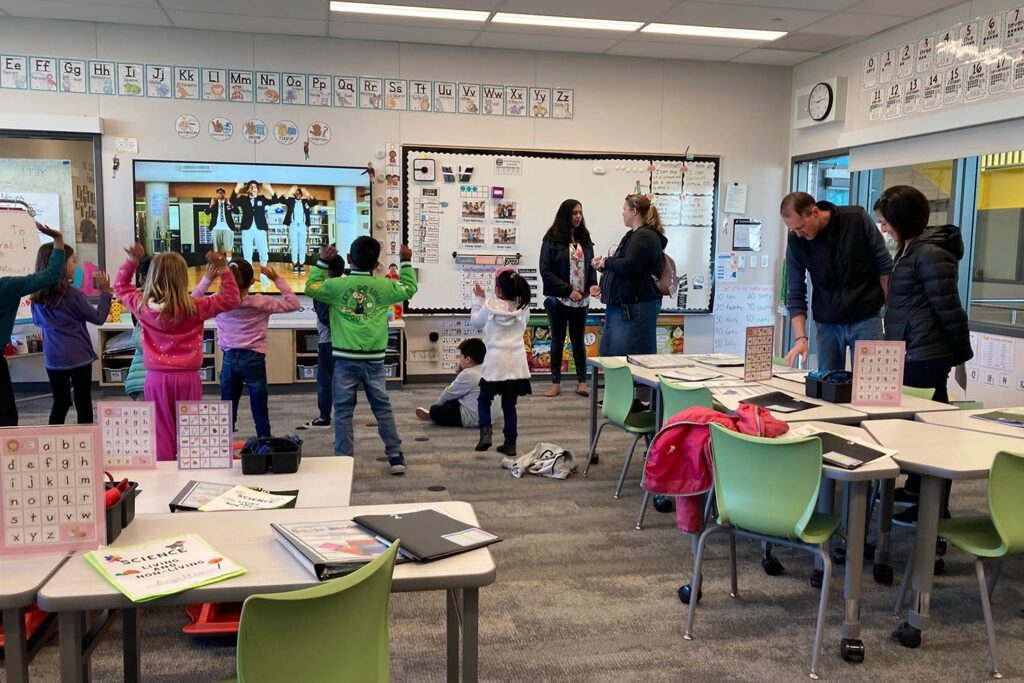

The RPLP takes place on the Agnews K-12 campus, which houses three adjacent schools: Agnew Elementary, Dolores Huerta Middle School, and Kathleen MacDonald High School. The campus is a 55-acre site that historically housed the Agnews State Hospital, a facility for adults with severe disabilities and mental illnesses. Opened in the 2021-2022 school year, part of the foundational vision for the schools was that they provide inclusive education, where students with a range of disabilities and learning needs are provided with the support to be able to learn in general education settings, rather than self-contained special education classrooms.

“My vision is that we stop limiting and siloing students with learning differences and those from underserved and historically marginalized groups. We want to allow them to have the same access to all the courses, to the high expectations and rigor, and to all opportunities that other students have,” said Kanavel, who has worked in the district for 35 years as a teacher, educational technology specialist, and instructional materials coordinator. “When you can do that successfully, it brings success to every student.”

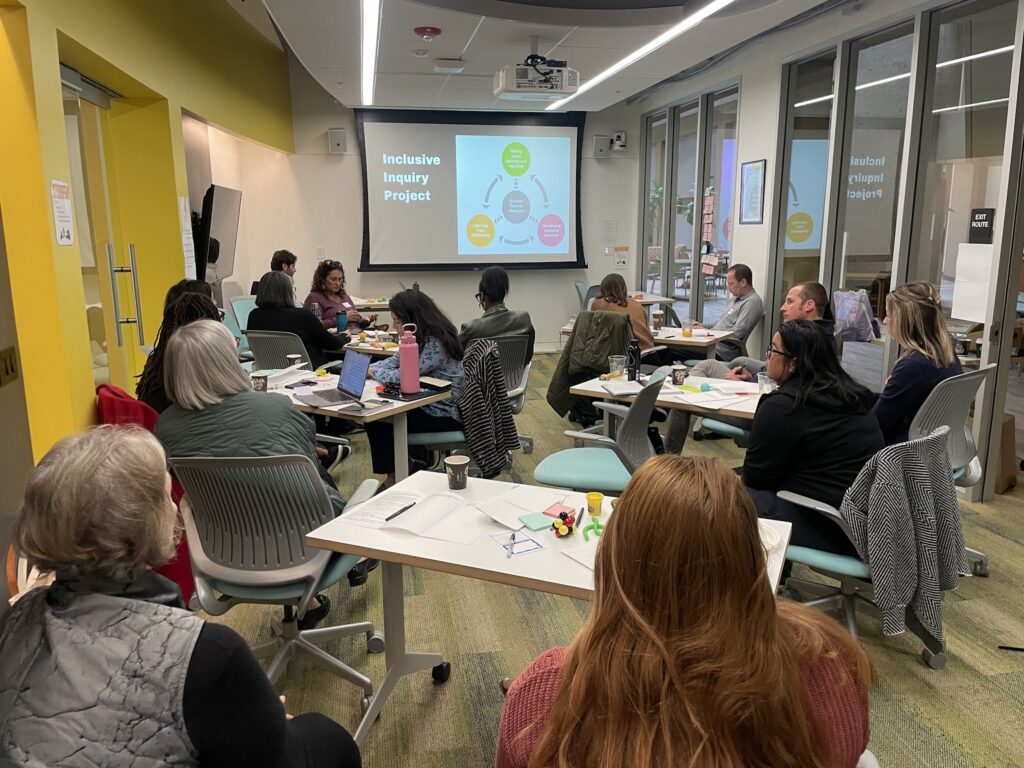

The steering committee of the RPLP, led by liaisons Nicole Henderson from Stanford and Sandra Velásquez from SCUSD, meets bimonthly to coordinate inclusive education explorations by educators and researchers happening across the three schools. At this meeting, the group touched base on 11 existing projects and brainstormed ways to assess the RPLP’s overall progress toward inclusion. The Stanford team shared updates on funding applications and possible ways of sharing research with the school; the educators gave insights into their end-of-year schedules and how the RPLP projects might fit in.

Learning from each other: A model for partnership

Kozleski has been doing education research in schools since 1988. Her model of collaboration involves working with district leadership to embed researchers in schools so that they can interact with the school community on a regular basis.

“A model of ‘collaborative construction’ allows us to build a suite of research studies with different faculty while advancing what the school is trying to achieve,” she said.

When Stanford signed the partnership agreement with SCUSD, Kozleski and Kanavel decided to call it a “research practice learning partnership,” an expansion of the concept of “research practice partnership” that has been a mainstay of education research. “The RPLP is more educator-driven, where people become part of the community and we develop projects together,” said Kozleski.

“We are learning all the time,” added Kanavel. “When you’re a classroom teacher, you don’t always have time or resources to make sure you are using best practices that are research and evidence-based, and this can result in achievement gaps. What the RPLP brings is the reminder of how important it is to have a data inquiry cycle to see what's working and adjust when necessary.”

The steering committee is a key piece of the collaboration model of the RPLP, with members of the committee representing the school community to bring questions and ideas they hear around the building to the forefront for researchers to explore. The committee includes educators from multiple grade levels and content areas, special education teachers, and school leadership.

In some cases, the Stanford team brings in existing projects to share with the schools, such as the Para Pro Academy and Rapid Online Assessment of Reading (ROAR), led by Stanford Accelerator for Learning Faculty Affiliates Chris Lemons and Jason Yeatman, respectively. The two projects have been piloted at Agnew Elementary and there are plans to expand them to the secondary level at Huerta and MacDonald.

Other projects emerge from the schools. In response to educator and family requests, Stanford researchers and school personnel co-created a project about social-emotional learning at Agnew and a career education program at MacDonald. While decisions in the RPLP are made in a democratic and shared way, ultimately the district and school leadership have authority as to what interventions are brought into the school.

Joe Young, principal of Agnew Elementary and a member of the steering committee, encourages his school’s educators, parents, and staff to dream big. “How lucky are we that we have a well-respected collegiate partner with a network of folks to tap into?” he says.

A lighthouse for inclusive education

One of the goals of the RPLP is to serve as a “lighthouse” to show the education community what a truly inclusive school could look like, and build a network with other schools and districts doing the same. A lighthouse inclusive school has students with a number of divergent needs who are able to be in mainstream classrooms and taught effectively by general education teachers.

Kozleski points out that many classroom practices that give access to students with disabilities are good for all learners. For example, describing one’s physical appearance when introducing oneself helps visually impaired learners, but also develops all students’ language skills.

“Inclusive practices are within the capacity of schools to do, but schools need to understand how important it is, make the time for it, and give educators permission to do it,” she said. She sees the lighthouse model as a way to show educators, schools, districts, and researchers what is possible.

Kanavel sees long-term mutual benefits for both the district and Accelerator researchers. “Based on what we learn together, I see us changing structures and systems to enact and broaden our vision of school as an inclusive place for all students, especially our students with learning differences,” she said.

To amplify the findings of the RPLP, Kozleski envisions research that emerges from the partnership being published in peer-reviewed journals across disciplines. The RPLP is already starting to share its knowledge with the next generation of educators; the STEP program plans to place teacher candidates at the Agnew K-12 campus in the upcoming school year.

“We are building a co-constructed definition of what inclusion is,” said Young. “But inclusion is a moving goalpost – how can we continue to be inclusive, every single day? How wonderful that we get to have the experience of recognizing and celebrating every new person who joins our community.”