At a meeting before the start of the school year at Abram Agnew Elementary School in San Jose, special education aides shared the strategies they planned to use to boost their effectiveness. One of Maria Ochoa’s goals was to initiate regular communication with classroom teachers.

“I want to make sure we’re on the same page, and I’m going to be keeping notes about our work with students,” she said.

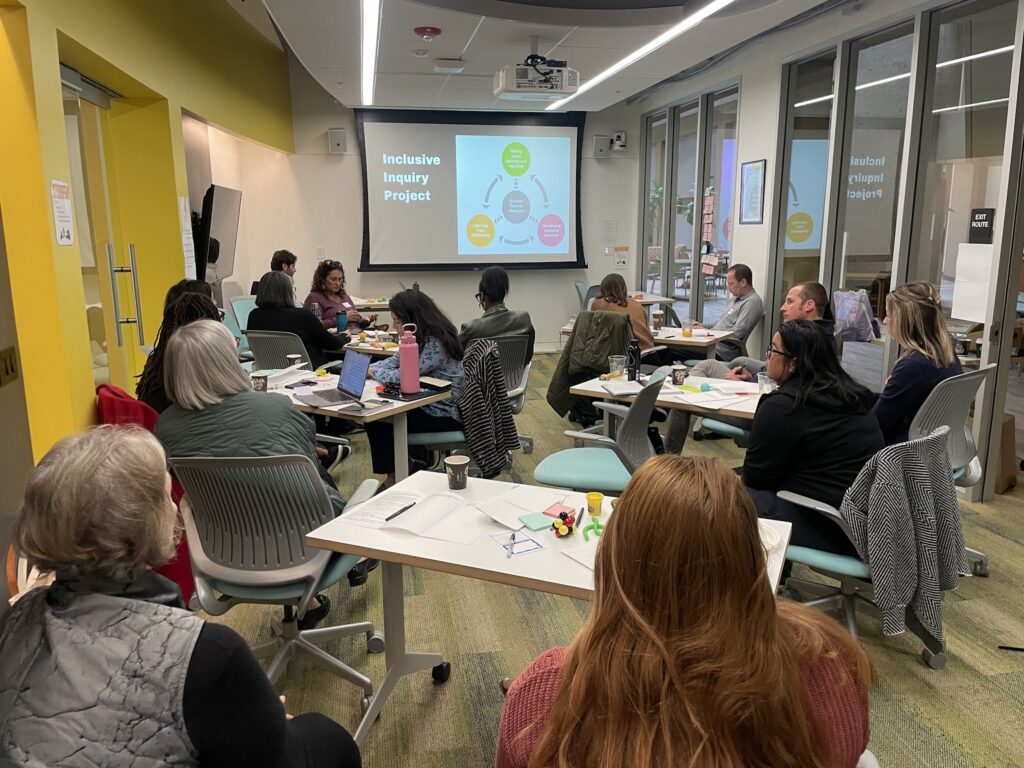

In August, Ochoa, along with 15 other aides or paraeducators, completed their final session of Para Pro Academy, a collaboration between Stanford University’s Graduate School of Education and the Santa Clara Unified School District, where they learned techniques and strategies for a role that Stanford Accelerator for Learning Faculty Affiliate Chris Lemons describes as an underutilized and important link to student success.

“The reason we are targeting paraeducators in this work is because they are some of the most critical staff in schools – they are where the rubber meets the road for improving outcomes for learners with disabilities,” Lemons said. “Schools infrequently devote sufficient professional development or coaching to this group.”

Unlike teachers, paraeducators are not required to have teaching credentials or even bachelor’s degrees, and they often receive little, if any, training on the job. And teachers, including those trained to provide special education services, often don’t receive guidance for working with paraeducators. The vision for Para Pro Academy is to empower paraeducators and facilitate their work with teachers to improve student learning.

The project is the first initiative in a research-practice learning partnership between Stanford and Santa Clara Unified District that will enable both Stanford faculty and educators to try ideas in real classrooms, improve on the ones that work, and then share them more widely.

Graduate School of Education Professor Elizabeth Kozleski, the faculty co-director of the Learning Differences Initiative at the Stanford Accelerator for Learning, said the partnership was designed to create a cycle of frequent communication and mutual learning.

“A community of practice is where everyone is asking the questions,” she said. Through their interactions, everyone can be curious and ask, in different ways, “How does learning happen?”

Seed funds from the Stanford Office of Community Engagement made it possible for paraeducators to attend the training sessions and receive coaching and educational materials, which will be available in the school’s library for use by other classroom aides.

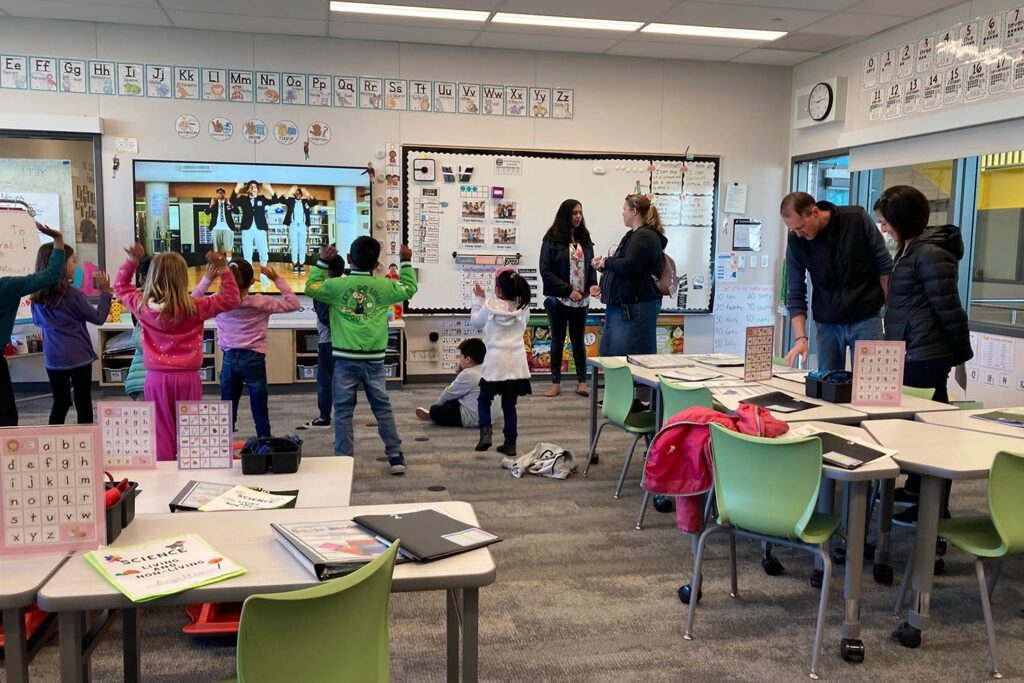

The shift toward inclusive classrooms

Federal law has mandated since 1975 that students with disabilities be educated alongside their nondisabled peers to the extent possible. But for many years, in California and across the country, special education meant separate classrooms, separate teachers, and even separate sites. As the move toward providing special ed services within inclusive classrooms gains momentum, paraeducators are key to supporting the students who in years past might have been placed in separate classes, Kozleski said.

At Agnew, where students with learning issues in 13 recognized disability categories learn side by side with other students, Principal Joe Young said the training program helped the school’s paraeducators focus on what they wanted to accomplish with their students – and with their own professional development.

“Clearly identifying goals during the Para Pro Academy has really supported their intentional efforts to improve their practice,” he said. The program has elevated the profile of paraeducators within the school as part of the team contributing to student learning, he said, and “it has really given them a greater sense of their impact.”

Reflecting on the first few months of the school year, Ochoa said that progress can be hard to measure with individual students because she changes classrooms regularly, working with students across the district. Detailed note-taking and close collaboration with teachers and other paraeducators have helped. “Luckily, my team keeps very open communication about the students we work with, so if we find techniques that work well for the student’s progress, we try to maintain that progress when we rotate working with the same students.”

This story was originally published by Stanford Report.