For high schoolers, there’s a lot riding on whether they pass Algebra 1 by the end of ninth grade. Students who fail the course are unlikely to meet college admissions requirements by the end of their senior year, and they’re less likely than others to graduate at all.

One school district in San Mateo County, Calif., is taking a novel approach to support students struggling in math. Instead of being put on a remedial track, those who enter ninth grade below grade level join their peers who are already at grade level in the same Algebra 1 classroom — with teachers who’ve been equipped through an intensive training program to help them all improve.

A study of the initiative, which was piloted at the Sequoia Union High School District (SUHSD) through a randomized controlled trial, showed that ninth graders in mixed Algebra 1 classes who entered below grade level went on to do substantially better on 11th grade math tests than their peers who were placed into a remedial course.

The study found that the initiative also increased attendance, the likelihood of staying in the district for all four years, and take-up of other college-ready math courses for the students who struggled initially. There was no indication of negative effects for the students who were at grade level in the mixed groups.

“We’ve had highly contentious debates about math pathways that simply accelerate or decelerate students, but much less attention on supporting teacher practice in ways that might broaden our sense of what’s possible,” said Thomas Dee, the Barnett Family Professor at Stanford Graduate School of Education (GSE), who conducted the evaluation with Elizabeth Huffaker, PhD ’24, now a research fellow at the GSE. “This study is a nationally relevant proof point of what high expectations and instructional differentiation in the classroom can achieve.”

Rethinking placement policies

The district, which serves a diverse body of nearly 9,000 students across four high schools, began re-examining its math placement policies in 2018 as part of a larger effort to promote critical thinking and collaborative skills, and to address achievement gaps across the curriculum.

“We wanted to create problem-solving classrooms where you can walk in and see students grappling with big ideas, and where they’re able to communicate their reasoning,” said Victoria Dye, executive director of curriculum, instruction, and professional development at SUHSD. “And crucially, we wanted to remove the racial and socioeconomic predictability of ninth-grade math placements.”

Enrollment in advanced high school math courses is highly stratified by race and socioeconomic status, with evidence showing that Black, Hispanic, and poor students complete fewer college-prep classes than their white, Asian, and affluent peers.

The GSE, in collaboration with the Stanford Accelerator for Learning, has partnered with nine San Mateo County school districts to conduct research on various educational challenges and opportunities through the Stanford-Sequoia K-12 Research Collaborative. At the start, researchers at the GSE’s John W. Gardner Center for Youth and Their Communities built a massive database to track student outcomes from elementary to high school, bridging gaps in knowledge about students’ progress from one level of schooling to the next.

The data archive makes it possible for all nine districts to see students’ experiences across districts and over time, and it allows researchers to study learning patterns and factors that predict different academic outcomes.

For SUHSD’s math initiative, researchers were able to study links between math course pathways and other measures, such as how students scored on state exams and whether they were able to complete college-eligible math courses. A project led by GSE Professor and Stanford Accelerator for Learning Faculty Affiliate Guillermo Solano-Flores studied the paths taken by English learners (ELs) in particular — especially long-term English learners (LTELs), or students classified as ELs for more than six years.

Different combinations of the math courses offered could result in about 80 possible trajectories — a number of which would leave students falling short of college admission standards, despite satisfying their high school graduation requirements. Solano-Flores and his team found that LTELs were significantly underrepresented in trajectories that would make them eligible for competitive colleges, even if they had already taken Algebra 1 in middle school.

The discrepancy between graduation requirements and college entry standards is often not clear to students and their families, especially those from other cultures, Solano-Flores said. “In Latin American and other countries, if you pass your mandated math courses in high school, you’ll be eligible for college. You don’t need to take extra classes to become eligible.”

Solano-Flores’ team recommended expanding efforts to communicate with families, especially with visual and interactive tools, to make sure multilingual students understand the consequences of certain course paths. SUHSD is now piloting a web-based dashboard that shows parents whether their student is on track for graduation and college readiness.

The researchers also raised concerns about national assessments used partly to inform ninth-grade placement decisions, because the tests weren’t designed for that purpose and, given the time it took for the district to receive the results, were administered about a year before the students entered high school.

“A lot can change in nine or ten months,” said Solano-Flores, who recommended the district use tests based on its own curriculum and population, timed more closely to the start of ninth grade.

His team also recommended more heterogeneous classrooms that combined students with different levels of English proficiency across math courses. This would provide more opportunities for ELs to simultaneously develop English and learn mathematics, Solano-Flores said.

Raising the floor and adding supports

The district piloted the Algebra 1 initiative in the 2019-20 school year, addressing the concerns Solano-Flores and his team raised about the placement test and class composition while making advanced pathways more accessible to all students, including ELs.

The initiative “raised the floor” by eliminating remedial algebra for students in the treatment arm of the study and implementing a robust preparation program for those teachers. (Ninth graders who entered high school above grade level had completed Algebra 1 in middle school; they were placed in geometry and not affected by the initiative.)

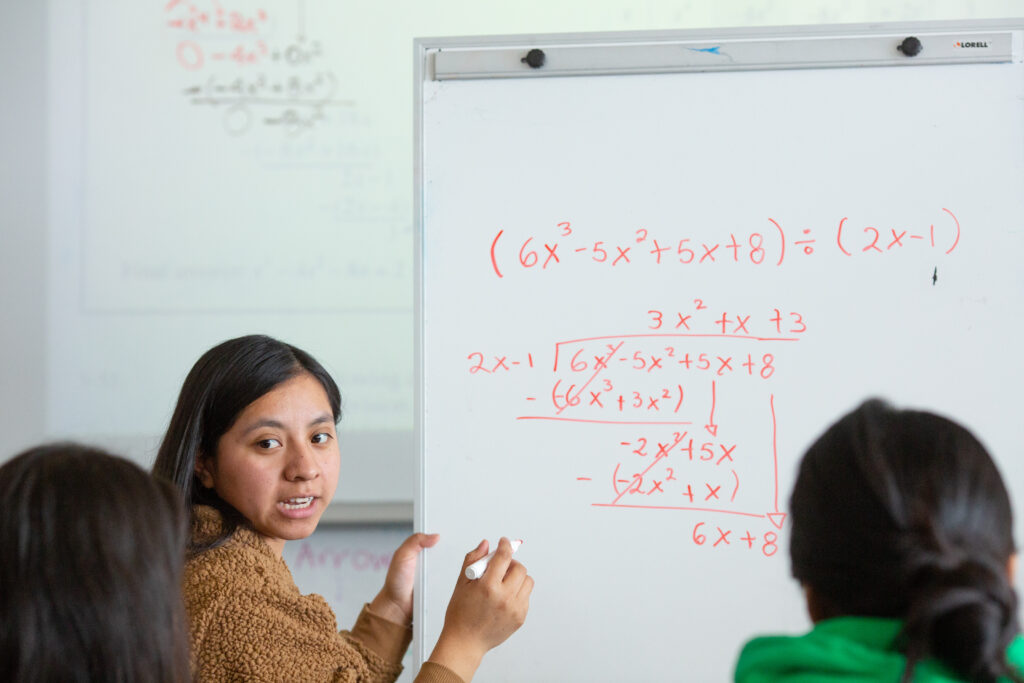

To start, teachers participated in two week-long intensive trainings over the summer with the district’s instructional coach and outside consultants. During the year, the teachers received on-site coaching, had an extra planning period each day to prepare for the mixed-level class, and met regularly as a cohort to learn and practice instructional strategies for “teaching at the speed of learning,” to help all students in differentiated classrooms improve.

“This study is a nationally relevant proof point of what high expectations and instructional differentiation in the classroom can achieve.”

Thomas Dee

Professor, Stanford Graduate School of Education

Many of the students in the study who initially tested below grade level in middle school matriculated to geometry in tenth grade, which wouldn’t have even been an option had they been in the remedial algebra class. Some students in the treatment arm did have to repeat Algebra 1 in tenth grade. “This was a very challenging course for them, much more rigorous material than they would’ve been exposed to in the pre-algebra course,” Huffaker said.

But by the end of 11th grade, students from the mixed-level Algebra 1 classes were 14 percent more likely than those in the control group to have completed Algebra 2, the next step toward college readiness.

When preliminary data showed progress for struggling students without any negative impact on the others, the district ended the randomization after one year and implemented the initiative for all students, extending the professional development program to all math teachers.

The district also worked with a consultant to develop a new math readiness assessment. Because the remedial course has been eliminated, the district no longer requires a placement test for students to enroll in Algebra, said Diana Wilmot, director of research and evaluation at SUHSD. “But we wanted to make sure we still could identify the kids who need more support, so we can allocate funding in a targeted way and for classroom composition, to ensure a heterogeneous group.”

The findings on improved attendance and students’ likelihood of staying in the district are consistent with other studies on school initiatives that promote a sense of belonging, the researchers said.

“Our teachers worked hard to disrupt the existing patterns of status that exist in the classroom,” Dye said.

As district leaders continue to track the effects of the initiative, the researchers expressed hope that the findings will draw attention to other dimensions of math policy beyond detracking.

“So much of the contentious math discourse is stuck on this ‘accelerate for all’ or ‘decelerate for all’ binary,” said Dee. “This research suggests that also being attentive to instructional core can be really impactful and unlock some of the false tensions that reductive framing has created for us.”

Thomas Dee is also the faculty director of the John W. Gardner Center for Youth and Their Communities, and a senior fellow at both the Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research and the Hoover Institution.