A team of three leaders from a non-governmental organization in Bangladesh sat across a round table from two professors from Brazil on a recent Monday morning at Stanford, sharing their plans for new research to help make education more inclusive for students with disabilities. A third team of researchers, from Argentina, had brought alfajores, cookies filled with dulce de leche and covered in chocolate, to the meeting. No one would guess the participants were jetlagged from their long flights; the room was buzzing with energy and ideas.

The Bangladeshi and Brazilian teams quickly found parallels in their research settings: the need for collaboration between education and other sectors such as health, housing, and transportation to support children with disabilities; unequal access to inclusive education despite national-level policies; and a plethora of quantitative data but the need for more qualitative data about their respective countries’ education systems.

Then they came to a key difference. The Bangladeshi team was most concerned about the social contexts of learners with disabilities. “Exclusion is a matter of attitude,” said Naila Zaman Khan, director of the Clinical Neurosciences Center at the Bangladesh Protibondhi Foundation. “We want kids with disabilities to be organically embraced at the family, social, school, and community level.” The vocabulary related to disability in Bangla, the local language, is often derogatory, she noted, and the team intended to study social factors through a qualitative study of schools and communities with and without inclusive education programs.

The Brazilian team was amazed. “It would be a dream to do research in communities,” said Flávia Faissal de Souza, a professor of special education at the Federal Rural University of Rio de Janeiro. It would be too challenging due to the prevalence of gang violence in her area, she said. But a lack of respectful terminology around disability in Portuguese, she said, was not an issue. “For us, that was a problem 10 years ago.”

Expanding the field of inclusive education

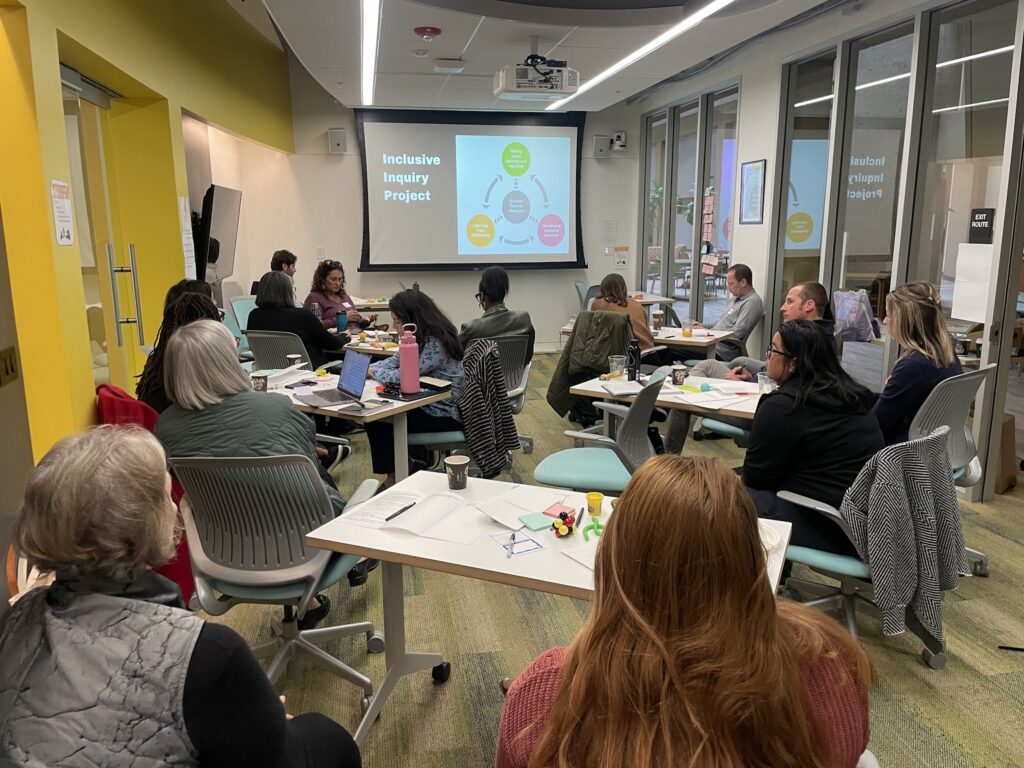

The teams had traveled to Stanford for a three-day gathering, “Charting the Geographies of Inclusive Education: Toward Sustainable Research Partnerships — A Research Conference in Honor of Judith Heumann.” Organized by and led by Elizabeth Kozleski and Alfredo Artiles, scholars at the Stanford Accelerator for Learning’s initiative on Learning Differences and the Future of Special Education, the workshop convened cross-sector teams of inclusive education policymakers, researchers, advocates, educators, and parents from seven countries in the Global South.

Inclusive education, outlined in Article 24 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons With Disabilities, is a framework for learners with disabilities that prioritizes inclusion in general education settings and ensures learners receive the necessary services to realize their “human potential and sense of dignity and self-worth.” By bringing together new research teams and a community of practice across national borders, the workshop intended to expand the body of knowledge about inclusive education to consider the diverse contexts of learners with disabilities across the globe.

“The kind of work that we wanted to do did not assume that knowledge from the Global North had direct applicability to the contexts that were to be studied,” said Kozleski, a professor at Stanford Graduate School of Education (GSE) and faculty co-director of the Learning Differences Initiative. “The world is connected in lots of different ways, but the fact is that pockets of things happen in some places that don’t travel to other places. We really want to know where seeds have been planted, where things are beginning to grow, and then look at the places in our world that aren’t getting the resources they need.”

Prior to the workshop, Kozleski and Artiles had spent 18 months designing its format, in collaboration with an advisory council of inclusive education experts from Stanford and beyond:

- Maya Kalyanpur, University of San Diego

- Federico Waitoller, University of Illinois at Chicago

- Kim Porteus, Nelson Mandela Institute for Education and Rural Development

- Charlotte McClain-Nhlapo, World Bank

- Gary Darmstadt, Stanford School of Medicine

- Daniela Gamboa Zapatel, GSE doctoral student

- Judith Heumann, disability rights advocate

The global teams then met virtually for six months, drafting research proposals with advising from the council. Once at Stanford, they finessed their research methodologies with support from GSE faculty Ramón Martinez, Sanne Smith, and Denise Pope. Faculty members Guilherme Lichand and Dennis Wall also advised the teams from Brazil and Bangladesh, respectively.

Judith Heumann, an internationally recognized disability rights activist, was involved in the project's conception and advocated for global level systems change for the rights of people with disabilities throughout her life. The convening was named in her honor after her death in March 2023.

Inclusive education in the Global South context: Emerging themes

Through collaborative sessions across three days, the seven teams found common themes and divergences between their Global South contexts that informed the development of their research proposals focused on inclusive education.

- The importance of defining terminology and conceptual frameworks. Inclusive education is a term created in the Global North and has varied definitions and interpretations across countries, sometimes referring to gender, race, caste, language, or socioeconomic status. The group discussed how their research might expand global understandings of inclusive education considering diverse contexts.

- Networks and relationships are crucial. Many of the projects were based in settings where the research team had been working for years and held deep relationships with local inclusive education coordinators, government officials, schools, and parents, enabling richer understandings of the context and more opportunities for data collection.

- Policies and their translation to practice can be fraught. While inclusive education is a priority of the United Nations and mentioned in national laws, many of the researchers reported that it is often translated and enacted much differently in local and school context. Several teams included an education policymaker or had direct lines of communication with government officials with whom to share their research findings and amplify the impact of their work.

- The strengths and agency of teachers, learners, and parents must be centered. Historically, deficit narratives have emerged about Global South countries and their education systems. The research teams aimed to amplify local needs, voices, and expertise and create new narratives related to inclusive education.

- Creative research methodologies can be of great value. Teams took a variety of approaches to data collection depending on their local contexts, connections, and expertise. In working with children with disabilities, emergent research methods were cited as very effective. The team from Argentina had experience analyzing student artistic productions (photovoice) and taking saliva samples to measure stress through cortisol levels, the first of which the team from India adopted into their proposals.

- Emerging technologies bring opportunity, but also potential dangers. Some teams, such as a group from Zambia, were excited about the potential of technology to support learners with disabilities, while others expressed concern about technology leaving behind learners without reliable devices and connectivity or replacing human teachers.

- Colonial legacies, inequality, and poverty are ongoing challenges across the Global South. Areas of commonality included the need to value local knowledge, unequal access to inclusive education along socioeconomic lines, and persistent challenges in identifying and designing learning for children with disabilities with other marginalized identities. In some but not all countries present, children with disabilities remain excluded from school. The importance of taking an intersectional approach to inclusive education and equity, keeping in mind race, gender, language, caste systems, and socioeconomic status, was reiterated throughout the convening.

Looking ahead: Inclusive education research across seven countries

At the conclusion of the gathering, each country team presented a research proposal. Next, they will seek funding to make their projects a reality. The research projects include:

- Mapping inclusive education at the county, school, and student level in the San Martín province of Argentina.

- Studying social inclusion of children with disabilities in a community with a seven-year inclusive education program in Bangladesh.

- Analyzing how inclusive education policies are interpreted and translated between the federal, state, and local levels in Brazil.

- Examining how grading practices in Guatemala discriminate against and exclude primary school children with disabilities, hindering them from progressing to upper grades.

- Developing a framework for inclusive education in the Indian context by documenting effective classroom practices of inclusive schools and disseminating them to schools that do not yet practice inclusive education.

- Comparing effective practices and challenges in inclusive education between urban and rural schools in Peru.

- Surveying effective low-cost, low-tech applications to support learners with visual impairments and building the capacity of teachers in Zambia to use them.

Artiles challenged the teams to think beyond the academy in the dissemination of their eventual research findings. "What do we need to do as a network to advance public scholarship?" he asked. "How do we bring our findings to legislators and professional associations within our countries and regions? How will you leverage your findings to push the system to use what you learn to start a process of change?"

A new network of expertise

The three days of collaboration reflected the Stanford Accelerator for Learning’s theory of change: to bring people together across sectors and geographies to ask new questions, envision new solutions, and expand the body of knowledge about learning.

Participants repeatedly emphasized that the most useful and meaningful part of the gathering was getting to exchange ideas with inclusive education leaders from other countries doing parallel work in disparate contexts. The three days established a new network to empower local expertise, seed capacity, and share knowledge about inclusive education.

“Somehow, maybe because of the structure of the work during these few days, or because of the people that are here, I feel that we can think together – that I’m not alone and our team is not alone,” said Faissal de Souza. “I think that’s the main principle to building a community and a network.”