A gong sounded in an upstairs classroom at the Stanford d.school. Students circled small round tables, perched on stools, with a whiteboard behind each group and sticky notes and markers spread in front of them.

There were undergraduate, master's, doctoral, and Distinguished Career Institute (DCI) students in the room, coming from fields as diverse as education, engineering, business, computer science, and humanities. The students' countries of origin included Barbados, Brazil, China, Egypt, India, Japan, Mexico, Morocco, the Philippines, South Korea, and the United States. For the interdisciplinary course, Design to Equip Learners in Under-Resourced Communities, each group of students was matched with a partner organization or school to co-design a solution to an educational challenge.

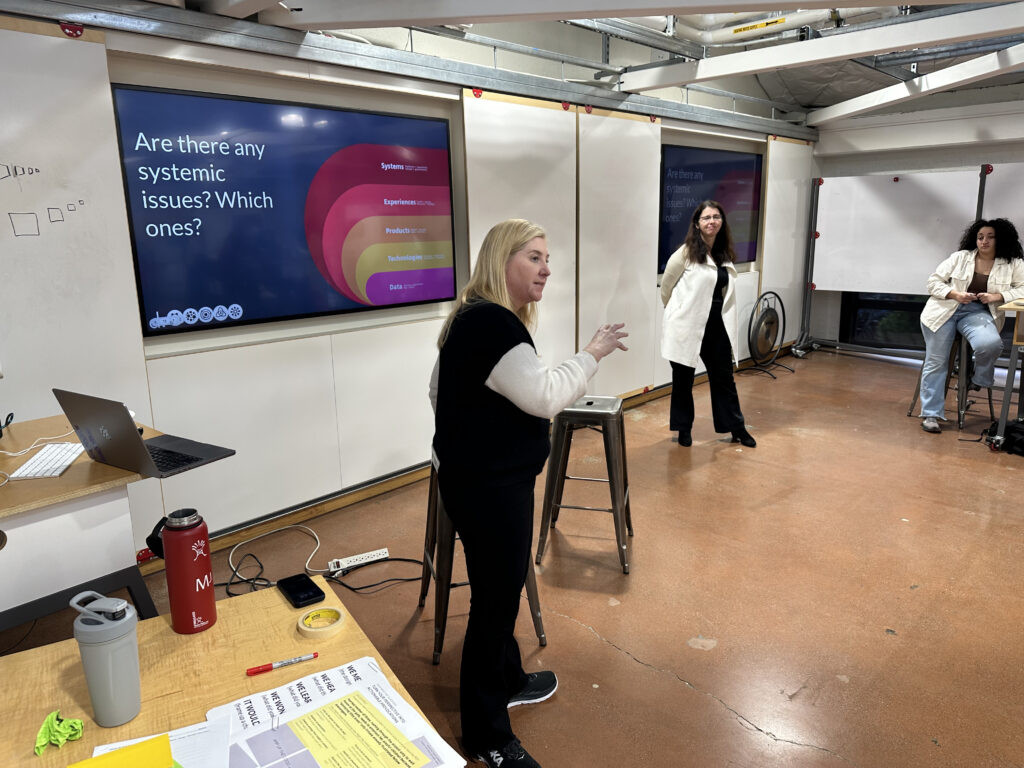

Isabelle Hau, one of the course’s three instructors, addressed the students, who had recently interviewed their community partners to better understand the challenges they faced. “Let’s reflect on our empathy interviews,” said Hau, executive director of the Stanford Accelerator for Learning, a university-wide hub housed at the Graduate School of Education (GSE) for researchers, educators, entrepreneurs, and others to collaborate on learning solutions. She put up a slide with prompts: What worked about the interviews? What didn’t work? What surprised you? What lesson did you learn for next time?

Each group shared reflections with the class. One group, working with the Sablayan branch of the Polytechnic University of the Philippines (PUP), reported that the rural campus had wifi issues and they had to send questions over email when the Zoom connection failed. Another team had been using an AI note-taking app, which they realized only provided 30 minutes for free, so only part of their interview was recorded. A third group interviewed an overworked charter school teacher in Los Angeles who spent most of the conversation venting, and they were struggling to figure out how to advance their project.

By the end of class, the teams were able to cover a poster with sticky notes describing the scope of their partner organization's main challenges, or “problem space.” They walked around the room, sharing their work with classmates.

As class ended, another of the instructors, Laura McBain, managing director of the Stanford d.school and K12 Lab co-director, asked the students to take a step back. “Take a picture of your poster,” she said. “Where is there empty space on it? Where are there areas of opportunity? Where can design play a role in addressing the problem?”

A trinity of flashlights

The course emerged after a series of collaborations between the d.school and the Stanford Accelerator for Learning, including an equity in learning design workshop and convening for teachers about generative AI. Hau and McBain decided to launch the new course to involve students in the work of co-designing education solutions and brought in Paul Kim, associate dean & chief technology officer at the GSE, as a third instructor. Kim had been working with GSE students for years on implementing and researching mobile technology in education in high-poverty areas in Mexico, Jordan, and Ghana, among other countries.

“The three of us got together and there was a spark,” said Hau. “I’m a strong believer that you find people you love working with and take it from there.”

Each instructor brought a different background and perspective as they helped the students develop their projects. McBain’s background in applying design processes to educational settings helped push the students toward novel and innovative solutions and a bias toward action. “She lives and drinks design,” said Kim.

Hau brought knowledge of entrepreneurship and learning science, encouraging students to come up with solutions that were both novel and grounded in research. Her background with entrepreneur and investor communities gave her an eye for the strategic development of new solutions.

Kim’s years of experience on the ground in schools across the world was key as the students navigated community partnerships. “He brings deep content and field expertise, and helps us ensure we aren’t causing harm,” McBain said.

“We got different ideas from different instructors,” said Alessandra Napoli, a doctoral student in mechanical engineering who researches STEM education. “When it felt like my team was in the dark, they each had a different flashlight.” According to McBain, bringing in instructors with diverse areas of expertise and crafting interdisciplinary experiences for students are key elements of the d.school’s problem-solving model.

The instructors drew on existing relationships with organizations around the world to help build partnerships for the students' projects. Hau had worked with Children’s Institute, which provides early childhood services, and Education Development Center, a global education organization with emerging entrepreneurship education projects in Senegal. Kim brought in Edify, an organization developing educational technologies in Ghana, and CIDE, which conducts national-level education research and supports education in rural communities in Mexico. Additional partners were part of Stanford’s Ed Equity Lab, including Camden Prep in New Jersey and Birmingham Charter in Los Angeles. Ramon Segismundo, a DCI student, brought in PUP Sablayan.

Seeking out the best solutions in context

The ten-week course started with overview sessions on the design process, learning science, and the education innovation landscape, paired with readings on inequities in education. Then the students conducted interviews with stakeholders from their partner organizations and prototyped possible approaches and solutions with their input. In addition to weekly class time, the teams met with the instructors for “studio hours” to further workshop and hone their solutions.

Carina Fung, an undergraduate computer science major and education minor with a focus on human-computer interaction, signed up for the class despite her already heavy course load. “It’s rare to get to work with real-world problems in my course of study,” she said. “I wanted to develop a really meaningful product to use in real-world situations. This class was too cool an opportunity to pass up.”

Fung went into the course expecting to design a solution based on technology. After her senior year of high school and first year at Stanford coincided with the COVID-19 pandemic, she developed a passion for understanding and improving education technology tools. However, she and her team quickly realized that a tech solution wasn’t right for their partner, PUP Sablayan. The rural university campus had ongoing challenges with wifi, bandwidth, and other technological resources.

“Even though I'm a big proponent of edtech, we didn't feel that this was the correct route to go,” said Fung. That was one of her key takeaways from the course. “The concept of humility in design has stuck with me. Even if you think it’s the best solution, it may not be in context.”

In the end, her team designed a community engagement initiative where teacher training candidates from PUP Sablayan serve as teaching assistants in a penal colony located nearby. Other solutions designed by student teams included an information and communication technology (ICT) course using storytelling and local folklore for young children in Ghana, a podcast recorded by and for teachers in rural Mexico, and a gamified English language learning app for Syrian refugee teenagers in Lebanon.

Embarking on a lifelong journey

McBain said she hoped the course helped to build deeper connections between Stanford and the community partners, laying the groundwork for continued collaboration. “We are in their journey with them and exist in mutuality with them,” she said. “That’s how we make change.”

Hau stressed the importance of involving students in building evidence-based education solutions, which motivated her to teach the course as part of the Stanford Accelerator for Learning.

“So far, the Accelerator has focused its theory of change on faculty driving change at scale, and this is a beautiful avenue,” she remarked. “What I would like to see more is tapping into the phenomenal students we have here at Stanford, and we are still just at the beginning of that opportunity.” Several groups in the course are continuing to develop their project as part of the Learning Design Challenge, another student-facing resource of the Accelerator.

“I want our students to understand how serious educational disparities are and work toward making the gap smaller and smaller,” added Kim. “Education doesn’t change just by innovation, which may not be sustainable or scalable. You also need compassion and commitment. I hope our students will embark on this lifelong journey.”