When San Francisco Unified School District created the Shoestrings program — an effort to reduce racial gaps in early childhood discipline — district leaders knew they were taking on an important challenge. What they didn't expect was that this work would reveal a new problem affecting schools across the country.

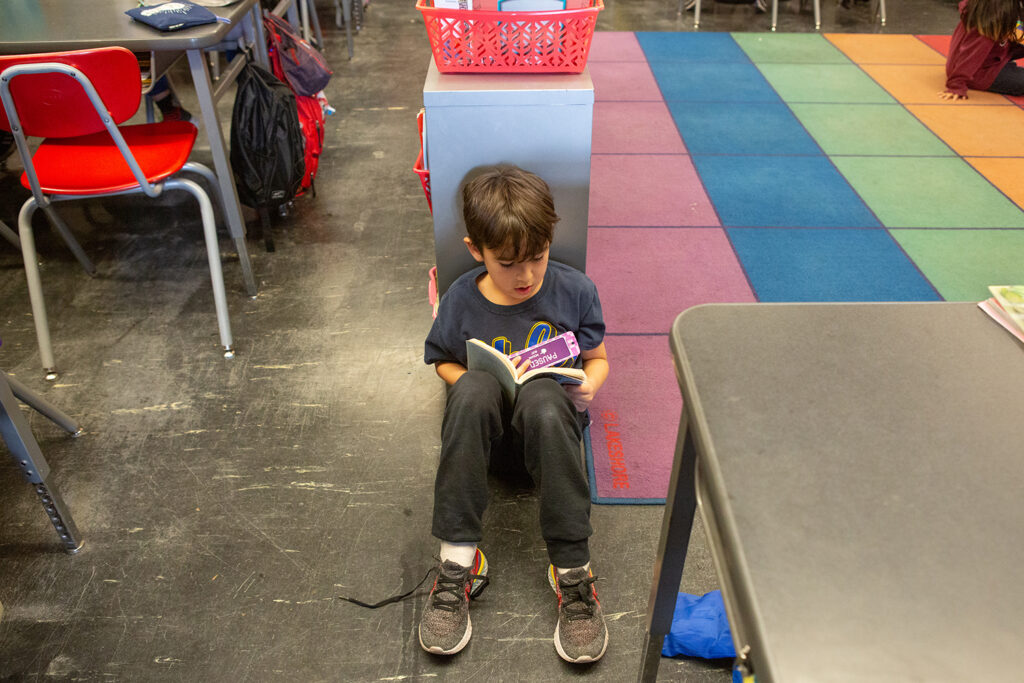

A new Stanford research study that focuses on SFUSD has found that schools may be using informal ways to remove students from learning, such as sending children home early or isolating them in hallways. This is often done without recording these actions, even as official suspension numbers decline. The study was published in AERA Open, a journal of the American Educational Research Association.

The discovery came as Stanford researchers studied Shoestrings, a program the district developed after it was sanctioned by the state for high suspension rates among Black students. What the researchers found pointed to a national issue: schools may be getting around suspension bans by using informal practices that disproportionately affect Black students while flying under the radar of official data.

"Regardless of intent, these practices undermine the developmental and learning opportunities of the most marginalized children, whose families already face hardships driven by pervasive systemic inequalities," said Jelena Obradović, one of the study’s authors. Obradović is a professor at the Stanford Graduate School of Education, a faculty affiliate of the Stanford Accelerator for Learning, and associate director of the Stanford Center on Early Childhood.

A national problem revealed through local partnership

Preschoolers are suspended more than any other age group in the United States, with young Black children historically the most affected. California is one of at least 17 states that have passed laws in recent years limiting suspensions and expulsions in all grades, and outlawing the practices for public preschools in 2022.

Previous research finds that exclusionary discipline, which is punishment that removes students from the classroom or school environment, can reduce student and family school connectedness and academic achievement. It also increases the likelihood of future discipline, dropping out of high school, and juvenile and adult incarceration.

While official state data generally shows declining suspension rates for California public school students, the reality is more complex. Schools are shifting away from traditional suspensions, which keep students at home, and leaning more toward positive behavioral interventions and restorative justice. But practices such as sending children home early or isolating them in other spaces continue — often without any official documentation.

While writing a case study about the Shoestrings program, the research team "started hearing things that surprised us," said study co-author Lily Steyer, who is now director of Child Policy at the Clinton Foundation. During interviews with teachers, behavior specialists, administrators and parents, they found that "on paper, suspension rates seemed to be going down, but in reality new forms of informal discipline were taking their place."

The discovery expanded what San Francisco — and districts everywhere — need to address.

“The findings have reinforced both the urgency and the direction of our work in SFUSD,” said Crystal Hawkins, director of the Shoestrings Children’s Center Early Education and Elementary Programs. Hawkins co-authored a set of policy recommendations with Obradović and Steyer based on the findings (see below).

She said the district is taking “intentional, system-level action” to eliminate exclusionary practices from preschool through 12th grade. That includes changes that are grounded in “developmentally appropriate, culturally responsive and preventive practices that center belonging and relationship-based support in early childhood.”

Types of informal exclusionary discipline

Researchers identified three categories of informal exclusionary practices happening in schools:

- Within-classroom: When a student is excluded in the back of the room, or not allowed to participate in normal classroom activities or discussions, or a parent is asked to come in to support the student, or classmates leave (for recess, lunch etc.) and the student is told to stay behind.

- Within-school: When a student is sent to a different classroom, or sent to be supervised by a staff member who is not a teacher, or sent to sit in the hallway unsupervised.

- Out-of-school: When a student is sent home, or told not to come to school, or put on a reduced schedule, or is transferred to a different school.

One school employee interviewed for the study said schools are “so scared of having bad suspension data, especially for African American students,” that educators engage in “clever” types of exclusion that “wouldn’t be officially documented as suspension or expulsion.”

Understanding the challenges educators face

The research revealed that teachers use exclusionary discipline for various reasons, with all educators interviewed citing class management and safety concerns, such as when children were hitting, biting, knocking down chairs, or making the classroom "not safe." Roughly half of teachers said they use it to help children regulate or manage challenging emotions or behavior by giving students "a place to take a breath," as one teacher said.

Educators also described significant barriers to moving away from these practices: lack of training and resources, persistent staff shortages, limited mental health support, burnout, and compassion fatigue.

"We need to stop punishing children when they experience big emotions and proactively teach them to understand their feelings and respond in safe ways," Obradović said. "At the same time, we have to acknowledge the emotional toll that this work can have on educators and provide them with ongoing training and resources that do not feel like one-offs or add-ons."

Policy recommendations for districts nationwide

Though this research focuses on early education in San Francisco, the problem isn't unique to early childhood or to SFUSD, according to Steyer.

“In talking with educators and researchers across the country, we began hearing that informal exclusionary discipline practices were showing up in districts nationwide, including in later elementary, middle school, and high school settings,” she said. “It prompted us to conduct a broader research review to understand the phenomenon of informal discipline across geographies and the full PreK-12 continuum.”

Steyer, Obradović and Hawkins co-authored a new set of policy recommendations offering federal, state, and district leaders ways to address and document exclusionary discipline practices. The report was published in late 2025 in the journal Child Policy Nexus, published by the Society for Research in Child Development.

The recommendations, which go beyond early childhood settings, include:

- Requiring schools to track and report informal exclusionary practices

- Ensuring schools hire adequate staff to support positive behavioral approaches

- Equipping teachers with better supports and professional development training

- Providing ongoing mental health resources for both students and educators

"As California expands their Universal Pre-Kindergarten (UPK) programs," Obradović said, "it is critical to put in place policies and system-wide supports that will protect young students from practices that can impede school success and cause lifelong harm."

This story was originally published by the Stanford Center on Early Childhood.

Authors not mentioned above for “De Facto Suspensions: Informal Early Childhood Exclusionary Discipline Practices in Public Preschool and Early Elementary Settings” are Maya Provençal, Stanford PhD student; and Francis Pearman, assistant professor at the Stanford Graduate School of Education. Read the full study here.

Authors not mentioned above for “Informal exclusionary discipline practices in US schools: Recent evidence and policy considerations” include Rebecca Gleit, Department of Sociology, Skidmore College; Crystal Hawkins, clinical program administrator at San Francisco Unified School District; Maya Provençal, Stanford PhD student; and Francis Pearman, assistant professor at the Stanford Graduate School of Education. Read the full report here.